Preachers denounced it. Aristocrats disowned it.

Yet it captured the hearts of the common people. Fueled by the fiery music of gypsy violins, the Csárdás also captivated and inspired great romantic composers like Brahms and Liszt, who made it famous throughout the musical world.

In Hungary and Slovakia the Csárdás rose to become the symbolic expression of the “national” soul. That’s a triumphant procession for a relative upstart among central Europe’s dances. After all, the Csárdás is hardly 200 years old. But while it’s certain that the dance didn’t ride into Central Europe with the conquering Magyar horsemen a thousand years ago, it’s also safe to say that it has real roots that spread deep and wide into older, perhaps ancient layers of music and dance.

Like all new dance styles, the Csárdás was born of a musical transformation. Musicologists now agree that Csárdás music is a mutation of earlier folk music. And, while this new music was born in central Hungary, it incorporated influences from as far away as the Polish Krakowiak.

The Csárdás is an improvised dance. The man leads his partner as he would in most “modern” couple dances. However, unlike the polka and the waltz – two dance fashions born around the same time – the Csárdás has a far richer repertoire of steps for the dancers to choose from. More importantly, the Csárdás maintains a tradition of individual and couple dancing that goes back to much older dances throughout Europe. In fact, Flemish peasants of the 16th century, freeze-framed by Brueghel’s art, seem to be performing dances that still come to life on the feet of old Transylvanian villagers today.

The roots of the Csárdás go back not only in time, they spread out geographically, incorporating elements of the Ugros dance from Hungary, the Forgatos and Invirtita from Transylvania and the Friska from Slovakia.

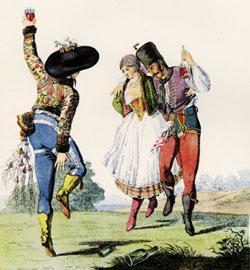

One of the striking characteristics of the Csárdás is that it has a slow and a fast part. And in the fast Csárdás, the partners often separate to dance apart, teasing each other in a romantic dance-relationship that brings possibilities for playfulness and enticement to the Csárdás. The man’s part in this love play often changes into a virtuoso performance that can include spectacular boot-slapping sequences. These male solos are not merely about showing off; they are the remnants of much older men’s dance traditions re-interpreted in the Csárdás.

The most ancient of these men’s dances were victory dances done with weapons, often swords. Gypsy traditions in Northeastern Hungary have kept alive a curiously exciting bridge between the weapons dance and couple dancing: a man and woman dance together, never touching, the man twirling a stick as he would in a fight; the woman defenseless, places complete trust in her partner, the dance itself her only weapon.

Although the Csárdás is known and loved in all areas of the Carpathian Basin, the local variants are often surprisingly different. In Transylvania, for example, mountainous terrain and bad roads still combine to keep villages isolated. The result is that the people of one village may not recognize the Csárdás done by other villagers a mere dozen miles away.

The Csárdás is a dance tradition whose domain stretches from Croatia in the south to Poland in the north; from Austria in the west to the Ukraine in the east. It can be simple and slow. It can be fast and furious. It can be romantic love play. It can be a dynamic exhibition piece. The music can be fiery, intense or exotic, but it can also strike the familiar chords played by café-gypsy orchestras resembling the music often heard in classical compositions of Liszt, Brahms and other composers.

The Csárdás is a complex, multi-layered, living tradition that’s still guaranteed to set toes tapping and hearts beating faster.